Finding the Horizon: Reviewing Assessment in this Time of Remote Teaching

We are living in a unique moment in the world’s history, to say the least. Some call the experiences associated with the coronavirus pandemic unprecedented. And while they are “unique or unprecedented,” they also can be frightening and frustrating.

These experiences are frightening because so much of our typical life is out of our control and we don’t know where these experiences are going. They are frightening for educators because many of us are working in unfamiliar territory–teaching students who attempt to learn while “confined” to their homes. This experience can also be frustrating for educators because we might be unsure how to teach students who are not physically present with us.

We will attempt to alleviate some of the fright and some of the frustration with the following discussion.

The first topic we will tackle is “assessment.” As we progress deeper and deeper into home learning, we ask the question of how we should assess student learning or student progress. At state and national levels, high-stakes testing has been suspended for the spring semester of the 2019-2020 school year. By March 20, the U.S. Education Secretary announced that K-12 schools would not be required to do standardized testing during this time of unprecedented social challenge. In a written statement, Secretary Betsy DeVos said,

“Neither students nor teachers need to be focused on high-stakes tests during this difficult time.”

Regardless of the status of high-stakes testing, teaching and learning continues. Educators provide learning experiences in a variety of formats for their students. Some schools and teachers provide weekly learning packets that students, with the assistance and supervision of their parents, work through independently. Some schools and teachers deliver instruction fully online, converting typical face-to-face instruction into online learning experiences. Others offer hybrid instruction, combining online instruction with paper learning packets.

As long as instruction is ongoing, assessment of student learning should occur. As educators concerned with the continued learning and academic progress of students, we likely ask two questions:

- is it important to assess progress?

- if it is important, how do we do it?

In terms of the first question, John Hattie and Gregory Yates offer a succinct response:

“As a professional, it is critical to know thy impact.”

- (Hattie and Yates, p. 69).

Hattie reviewed thousands of educational research studies in an attempt to ascertain the most impactful practices used by educators (2009). In his review he determined effective sizes for various practices; that is, the size of the impact on learning associated with various practices. Based on Hattie’s work, Hattie and Yates assert that knowing whether a student has learned from our teaching is important if we want to know if our teaching makes a difference in a student’s learning. They conclude that we must assess whether a student has learned from the instruction and the learning experiences we provide if we are going to be able to offer learning experiences that have the potential to lead to real learning on the part of students.

Designing effective assessments is a challenge. Designing effective assessments is even more of a challenge given the current nature of our instructional environment. With students learning at home, typical summative assessments, end-of-unit or end-of-the-week tests, are more difficult to design and deliver. Questions about summative tests, and quizzes for that matter, that are taken at home, with or without adult supervision include:

- “How can we develop tests that reflect what we teach when it feels like we cannot effectively control that which we wish to teach?”

- “Can we control assessments such that students will not take advantage of a loosely supervised setting?”

- “Will typical test formats be suitable for at-home assessment?”

Perhaps we have an opportunity to think differently about assessment, or testing. As our students work at home, we might ask, “How can I assess what a student has learned or what she knows about the content I’m seeking to help them learn?” This begs the question, “What is the most important idea that I want my students to know as a consequence of engaging with (i.e. doing) the work they do at home? As we answer these questions, our assessment of learning serves the purpose of learning.

In future reflections, we’ll consider a variety of topics associated with assessment while learning at home, including:

- What is the role of clarity in assessing learning? How does one offer clarity to lessons and learning when students are learning at home, rather than in school?

- How does assessment encourage the development of internally motivated and self-regulated learners? And, should assessment serve to do that?

- How does formative assessment serve teachers, so they can “know thy (their) impact?”

- What tools can we use or can we develop that will help teachers know their impact while their students learn in an at-home context?

We leave you with an encouraging peek into one school’s current conversation: this West Michigan school is acknowledging the difficulty of assessing at-home learning, acknowledging the bumps and bruises teachers might be feeling. The school principal has listened to the teachers’ concerns and is providing clear direction, empowering teachers to ignore potential distractions. Teachers are being encouraged to look straight ahead while crossing the choppy waters we’re finding ourselves in for the rest of the school year. You might say we are all developing our sea legs as distanced teachers. In this unusual time, we can remember the old seafarer’s trick of keeping our eyes on the horizon. As you read below ask yourself: What is this school’s horizon, and which distractions are they hoping to avoid?

Throughout our future reflections on assessment, we hope to provide navigation that helps us recognize and address potential distractions and pitfalls in the assessment process, obstacles that could potentially lead us off track during this unusual time of remote education. We hope to encourage teachers and administrators to focus on our shared goals, provide comforting permission to ignore practices that do not help us accomplish these aims, and explore research-based formats that help support our focus.

The following letter was written by Aaron Meckes, a principal at one of our member schools, to his high school teaching staff.

Hi everyone,

I have been reflecting on the discussion that occurred in our meeting on Monday morning with regard to many of you feeling overwhelmed by the amount of grading needing to be done. I also have been thinking about our students’ workload, what we are asking them to do right now, and the sustainability of it for all of us.

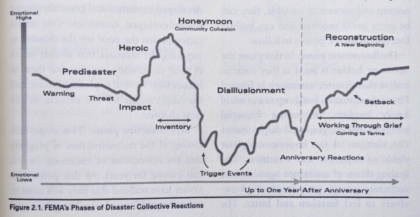

I can’t imagine I am the only one who has begun to feel “different” the past few days. I’m sure it is manifesting in many different ways; for me, I’ve noticed it in a lack of patience. I have noticed myself reacting quickly with anger toward things that normally would evoke grace and patience. This graph was shared with me last week and I’ve found it to be a helpful reference:

It seems likely to me that the past two weeks were spent in the Heroic and Honeymoon stages, and we’re now moving toward Disillusionment. I’m frustrated, and I know many of you are, too. It’s important to recognize our students are feeling this as well.

I think one way we can support ourselves and support our students is to ask, “What is actually most important?” I think of two answers as it relates to our work with students. The first answer is care. We have mentioned several times over the past few weeks that we believe this is part of what is distinctively Christian about the South Christian response to and posture toward this situation. We care deeply for students and their overall health. We care for their physical health, and it has driven us to comply with the State of Michigan’s safety standards during this time. We care for their spiritual health, so we have provided prayers, devotions, and faith-infused work. We care for their mental health, and it has driven us to pray for and reach out to every individual student, every single day. It has also driven us to continue their learning because we believe that continuing school is a faithful response to our current situation. Learning is what we’re about as a school, and we believe it gives purpose and meaning as God’s children.

This is why my second answer to what is most important is learning.

My challenge is that you design your class in such a way that prioritizes learning over compliance. I do not believe you need to have students produce or turn something in every day. Some of you may be asking, “But how will I know if they did the work?” and the reality is that you may not--but that is actually okay if our priority is learning and not compliance. What I am saying is that right now, accountability and compliance are not the main priorities. We are in a time unlike any other, and while accountability and following instructions are essential and critical, right now they are not the priorities. Our priorities are care and learning.

I don’t claim to know how to do this well, but let me give you a few examples to show you how I’m thinking about this and how we might emphasize learning over compliance.

Math

Today, I introduced the quadratic equation. On page 92 of your book, there are 30 problems involving the quadratic equation. Do as many of them as you feel you need to in order to get it. First thing tomorrow, I will give you two quadratic equation questions to answer for a grade.

This gives an opportunity for students who need more practice to have plenty of opportunities. It also gives permission for students who get it quicker to just do a few problems and move on to something else. The reality is that some students might be able to do 0 practice problems and still get 100%. But if we’re focused on learning and not compliance, that really shouldn’t matter. They learned it! That's a reason to celebrate. At the same time, you have made access to the information equitable to all by providing an opportunity to practice on multiple problems.

Literature

This week, you will read chapters 4, 5, and 6. Go at whatever pace works best for you, but have all of it read by Friday morning. On Friday morning, I will send you three reflection questions on a key idea from each of these chapters. Responses will be due Monday.

Do I have any idea if the kids did the reading? No. Will I be able to tell if they learned it? Yes. Is it possible for them to write coherent answers without reading? Maybe. Their answers might not be able to tell me if they were compliant, but their answers CAN tell me if they learned it.

Biology

This week we’re working on basic genetics problems. I’ve linked several resources and videos on Google Classroom for your reference. I’ve also posted a 6-page worksheet with practice problems for you to complete. On Friday, we will meet to have a quiz. The quiz will include one question on dominant/recessive, one question on sex-linked traits, and one question involving multiple alleles. There are several practice problems for each of these, and I can provide more upon request.

Will the assessment on Friday tell you if they’ve learned it? Yes. Will the assessment tell you if they actually did biology work during the week? No. Again, it is entirely possible for a student to do 0 work all week and get 100% on the assessment. The key here is that they learned it. Hooray!

I want to emphasize the following:

- When we value learning over compliance, busy work goes away and all work becomes meaningful.

- Grading becomes more sustainable because daily check-ins for compliance are not necessary.

- This approach is equitable because all students have the same access to the teacher, to resources, and to practice opportunities.

- This approach actually puts the ball in their court, not yours, and empowers the students to take control of and responsibility for their own learning.

Accountability is important. The ability to pace, follow directions, and stay engaged is important; however, I am not sure they need to be our priority right now. The point of this message is to provoke some thought and challenge you to think about how you might have students be accountable for learning but not busywork--how to prioritize learning over compliance.

Thank you for your continued work and dedication to keep kids growing and keep kids connecting.

A special thank you to Aaron Meckes for sharing his letter and leadership.

Phil Stegink

Teacher Consultant, Special Projects

Phil Stegink works on special projects for All Belong and is an assistant professor of special education at Calvin College.

High stakes testing can be defined as “any test used to make important decisions about students, educators, … commonly used for the purpose of accountability.” https://www.edglossary.org/hig...

Hattie, J. & Yates, G. (2014). Visible Learning and the Science of How We Learn, New York, NY: Routledge.