Why Inclusive Education Requires More than Head Knowledge

Today we asked disability advocate, author, and emeritus professor of special education David Anderson, Ph.D. to share why inclusive education requires not only practical knowledge for Christians, but also a transformed view of who we believe our students to be.

I’ve found that most programs designed to promote inclusive education build from what Amos Yong (2011) called a normate bias: an unquestioned worldview that views able bodies and minds as the ideal, causing people to hide their own weaknesses and limitations, and view disability as tragedy. Research has found that efforts to include children with impairments in the general education classroom are beneficial to students with and without disabilities. Using the concepts of universal design for learning (UDL) and differentiated instruction (DI), response-to-intervention (RTI), and collaborative teaching, educators can provide an appropriate education to all students—culturally, linguistically, and economically diverse as well as diversity in ability from impairment.

Nevertheless, there remains an unspoken belief that impairments need to be “fixed,” or disabilities “remedied,” in order for students with unconventional minds or bodies to fit in with others in the classroom. Many teachers, while agreeing in general with the idea of inclusive education, feel they are being asked to do something for which they have not been prepared, nor had they envisioned when deciding to become an educator.

Inclusion Involves Head–Heart–Hand

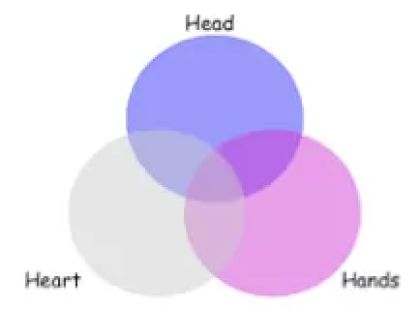

Synthesis of head, heart, and hands toward inclusive praxis (Pudlas, 2009).

Ken Pudlas of Trinity Western University spoke of a head–heart–hand linkage as a necessary element of inclusion (Pudlas, 2009). Head refers to what we know—about disability, about teaching methods, about how children learn, etc. This would include the practices of UDL, DI, RTI, and collaboration skills. However “head knowledge” does not guarantee that teachers or schools are truly inclusive. True inclusion begins not with the head but with the heart.

Successful inclusion is not built from what we know, but from who we are, and who we believe our students to be. Heart principles that should inform our Head and guide our Hands (praxis) include biblical concepts of interdependence, community, hospitality, and justice and reconciliation (cf. Anderson, 2012).

Interdependence

Interdependence leads to valuing and honoring each student, not because of what they can do or contribute, but because they are persons created in the image of God—regardless of ability or disability. Interdependence provides a model for the classroom ethos we desire, whether teaching in a Christian or a public school and has definite implications as to how classrooms and educational instruction should be structured to encourage inclusion.

Community

An inclusive community recognizes the gifts and talents, as well as the needs, of all the students. A community characterized by caring will be one in which everyone, students and teachers alike, plays a role in supporting others. Each student will experience an atmosphere of togetherness in the classroom and school.

Hospitality

Hospitality will be shown by making appropriate accommodations and modifications for all students as necessary (recognizing that what is helpful to a student who has a disability will also be of benefit to others) and through promoting friendships among the students—true friendships, not those simply based on helper–helpee relationships. The classroom should display “activated kindness,” characterized by protection, emotional support, empowerment, and personal commitment on the part of the teachers(s).

Justice and Reconciliation

Biblical justice will be demonstrated in an interdependent, hospitable, classroom community that shows special concern for those who are weaker and may feel powerless or oppressed by others and seeks to break down attitudinal barriers to promote reconciliation between those with and without disabilities.

With the Head being guided by these Heart attitudes, the Hands are enabled to consistently practice inclusion—something we do because of who we are. “Different” students are welcomed as an equal part of the classroom. They are not seen as a burden, but as a privilege and as an opportunity for teachers to further their professional development and all in the classroom to experience the “real” (though fallen) world in which disability is “normal.”

References

- Anderson, D. W. (2012). Toward a theology of special education: Integration of faith and practice. Bloomington, IN: WestBow Press.

- Pudlas, K. (2009). Head and heart and hands: Necessary elements of inclusive praxis. Journal of the International Christian Community for Teacher Educators (ICCTE), 3(1), http://icctejournal.org/issues/v3i1/v3i1-pudlas/.

- Yong, A. (2011). The Bible, disability, and the church: A new vision of the people of God. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans.

David W. Anderson

David W Anderson, Ed.D., is Emeritus Professor of Special Education, Bethel University, St. Paul, MN, where he served for 15 years as Director of Graduate Programs in Special Education. He is also President of Crossing Bridges, Inc., an international ministry focusing on issues of disability and special education, which seeks to promote inclusive practices in churches and schools.